The secret to Alexandria, if classical historians are to be believed, lies in a golden casket. Studded with jewels and small enough to hold in one’s hands, the casket was a war trophy found in the lodgings of vanquished Persian king Darius III more than 2,300 years ago. The man who defeated Darius, Alexander the Great, locked his most treasured possession – the works of Homer – inside it.

The secret to Alexandria, if classical historians are to be believed, lies in a golden casket. Studded with jewels and small enough to hold in one’s hands, the casket was a war trophy found in the lodgings of vanquished Persian king Darius III more than 2,300 years ago. The man who defeated Darius, Alexander the Great, locked his most treasured possession – the works of Homer – inside it.

Soon after conquering Egypt, Alexander had a dream in which Homer visited him and spoke lines from The Odyssey. Among them was a reference to the Egyptian island of Pharos in the Mediterranean, and so the next morning Alexander travelled to Pharos and stood upon its rocks, clutching the golden casket and staring out at a scrappy, forgotten stretch of coastline. After a long silence, he nodded. From these shores, the most remarkable city the ancient world had ever seen was about to rise.

Today, the original Alexandria lies buried beneath two millennia of urban evolution; the building blocks of its oldest temples and monuments have been carried as far afield as Cairo, London and New York, or else shattered by earthquakes and military invasions, or submerged under the sea. To understand the ancient city, archaeologists have had to peel back the modern one – along with deep and often contradictory layers of myth and folklore. Few metropolises are as steeped in legend as Alexandria, not least because few metropolises have ever attempted to gather together the world’s stories in one place as Alexandria once did, writing a new chapter of urban history in the process.

“Alexandria was the greatest mental crucible the world has ever known,” claim Justin Pollard and Howard Reid, authors of a book on the city’s origins. “In these halls the true foundations of the modern world were laid – not in stone, but in ideas.”

Although it is ancient Alexandria’s individual showstoppers – the lighthouse, library and museum – that are best remembered and celebrated in our own time, the city’s influence on contemporary life truly begins with its overall design. Alexander’s chief architect, Dinocrates, envisaged an epic gridiron that would knit together public space and private, spectacle and function, as well as land and sea. EM Forster, who became one of Alexandria’s most famous chroniclers in the 1920s, called it “all that was best in Hellenism”. Yet Dinocrates’ masterpiece very nearly sank without a trace before the first slab had ever been placed within the sand.

In the absence of chalk to mark out the shape of the new city’s future roads, houses and water channels, Dinocrates used barley flour instead. But as quick as his surveyors could calculate the relevant angles and his labourers could scatter the requisite lines of grain, flocks of sea birds swooped down and snaffled this life-size blueprint for themselves. Many on the ground considered it a terrible omen for the settlement which was to bear Alexander’s name, but the general’s personal soothsayer took a different view: the birds’ feeding frenzy, he explained, was a sign that Alexandria would one day provide sustenance for the whole planet.

And so work continued, and before long those sea birds were gazing down at a frenzy of construction. Sites were allocated for Alexander’s royal palace, temples for both Greek and Egyptian gods, a traditional agora – both a commercial marketplace and a centre for communal gathering – as well as residential dwellings and fortification walls. Canals were cut from the Nile, with rivulets diverted under the main streets to supply the homes of the rich with a steady provision of fresh water.

And so work continued, and before long those sea birds were gazing down at a frenzy of construction. Sites were allocated for Alexander’s royal palace, temples for both Greek and Egyptian gods, a traditional agora – both a commercial marketplace and a centre for communal gathering – as well as residential dwellings and fortification walls. Canals were cut from the Nile, with rivulets diverted under the main streets to supply the homes of the rich with a steady provision of fresh water.

On one level, Dinocrates’ plan for Alexandria was a cut and paste job, following the typical pattern of many of the Greek cities he was familiar with. Dinocrates was a student of Hippodamus, the man responsible for building the great Athenian harbour at Piraeus and often referred to as the father of urban planning. According to Aristotle, Hippodamus was the man who “contrived the art of laying out towns”, though the compliments ended there; the old philosopher went on to accuse Hippodamus of living in ‘a very affected manner’, and cited his ‘flowing locks’ and ‘expensive ornaments’ with disdain.

Hippodamus and his school believed that designing cities meant more than just sketching out the boundaries of the relevant site; planners had to think about how the town was going to function, not only logistically but politically and culturally as well. In the eyes of Hippodamus, streets were not just by-products of houses and shops but centre-points in their own right: a showpiece of efficient urban governance. But whereas Hippodamus was largely confined to piecemeal projects, transforming small sections of older cities from within, at Alexandria Dinocrates was offered a blank canvas – and a chance to put his master’s innovations into practice on an unprecedented scale.

Dinocrates’ genius was to extend the lines of his gridiron right out over the water, building a 600ft wide land bridge – known as the heptastadion, because it was seven times the length of a Greek stadium – out from the mainland to the island of Pharos and creating two immense harbours either side of the causeway. The level of integration between all the city’s various elements was profound. “You have the heptastadion forming the harbours, the harbours protected by the lighthouse, and the line to the lighthouse running back into the city’s main grid-plan on the same orientation,” says Dr Judith McKenzie, of Oxford University’s School of Archaeology and author of The Architecture of Alexandria. “It was a package deal, and it worked.”

Vitally, Alexandria’s success lay not only in its Grecian roots but also in its Egyptian influences. The tale of Alexander’s golden casket has been passed down the generations, but in reality the selection of the city’s location must have relied on local knowledge and expertise just as much as it did Homer. Not only did the new city form a perfect nexus between the relatively insular Egyptian pharaonic kingdom inland and the maritime trade empire of Greece and the Mediterranean beyond, but its roads were angled to maximise circulation of the sea’s cooling winds, and its buildings soon melded the best in western and eastern architecture. The famous octagonal walls of the ancient lighthouse are replicated today on countless minarets throughout the rest of Egypt, and on many of Christopher Wren’s church spires in Britain.

In whose image was the city created?

In the years to come, as Alexandria’s riches and reputation spiralled, its most famous institutions took shape: a musaeum (literally, a ‘temple of the muses’) which brought together the leading scholars in every academic discipline, and within it a library, believed to be largest on earth and sustained by the royally mandated appropriation of any books found on ships which came into the city’s port.

But Alexander himself would never live to see these marvels, or indeed the city which he founded. Soon after Dinocrates began laying out his lines of barley flour, the general travelled on to consult the oracle at Siwa, deep within Egypt’s western desert, and then headed east to new colonial campaigns in Persia and India. Within a decade, he had died in Babylon; his successor in Egypt, Ptolemy I, orchestrated an audacious kidnap of the body as it was en route to burial in Alexander’s native Macedon (modern-day northern Greece) and brought it instead to Alexandria where it was ensconced in a colossal tomb.

The fate of Alexander’s corpse is a window on to a darker side of Alexandria, one that was less about intellectual endeavour and urban modernism, and more focused on harnessing the city as a vehicle for autocratic power and the entrenchment of divine rule. Ptolemy wanted Alexander in death because it helped legitimise his own authority in life. Whereas the original Hellenistic town was intended as a polis in which autonomous citizens enjoyed an equal say in decision-making (unless, of course, they were female, foreign or enslaved), Alexandria became a template of urban absolutism – its regimented layout and carefully-demarcated quarters a display of control from above, not democracy from below.

“What was left of the old urban drama was a mere spectacle,” argues urban historian Lewis Mumford in his seminal The City in History. “In the old polisevery citizen had an active part to play: in the new municipality, the citizen took orders and did what he was told.” In Mumford’s eyes, the formal order and beauty so perfectly embodied by Alexandria on the outside reflected the disintegration of the real, messy freedom once promised by cities deep within.

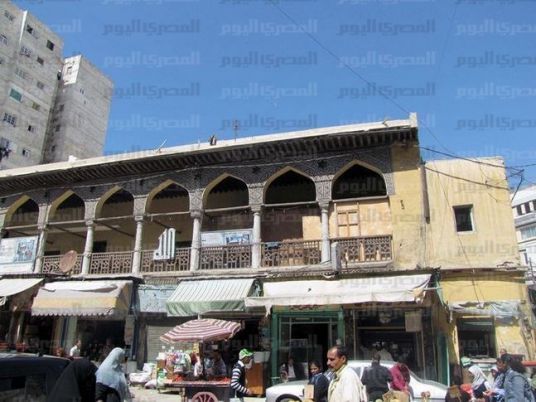

That tension, over whether the design of our cities best serves its residents or its rulers, has persisted down the centuries and continues to colour Alexandria today. Now home to nearly 5 million people, and the second largest metropolitan area in a country racked by mass rebellion and urban revolt in recent years, Alexandria remains on the frontline of competing visions of what thoughtful urban planning should really look like.

That tension, over whether the design of our cities best serves its residents or its rulers, has persisted down the centuries and continues to colour Alexandria today. Now home to nearly 5 million people, and the second largest metropolitan area in a country racked by mass rebellion and urban revolt in recent years, Alexandria remains on the frontline of competing visions of what thoughtful urban planning should really look like.

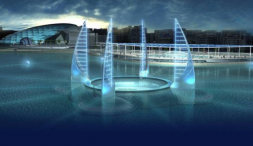

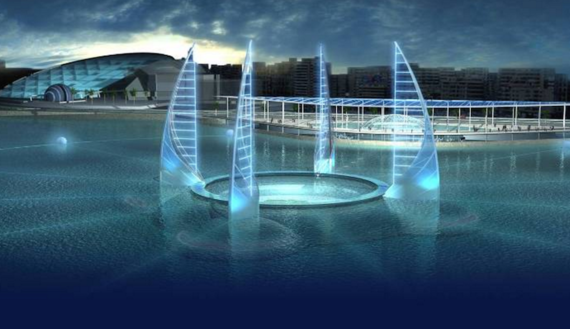

Last year a scheme was unveiled to rebuild the long-lost ancient lighthouse in its original location – part of a grand redevelopment project involving major new shopping malls and a high-end hotel. Critics insisted that the proposals failed to take into account the modern city’s complex informal economy and fragile architectural history, and pointed out that the decision was being taken without the input or agreement of residents. “The reality is not about amplifying Alexandria’s rich cultural history,” argued Amro Ali, an analyst of urban politics in Egypt, “as much as it is about which aspects of its history can be vulgarly commercialised at the expense of the public good.”

As Ali has noted, Alexandria’s contemporary power-brokers would be wise to read up on the details of the ancient lighthouse, which was finally completed a few decades after Alexander first stood on the shores of Pharos and decided his great metropolis would be built here. As was customary, the lighthouse’s architect, Sostratus, officially dedicated its construction to Egypt’s royal family on a plaster plaque near the entranceway.

But underneath the plaque, Sostratus secretly carved a second inscription into the stone: on behalf of “all those who sailed the seas”. The question of whose interests our urban spaces are really planned for has remained a live one ever since.

(www.theguardian.com)

Hosted by Alexandria’s Fine Arts Museum, one of the leading cultural and artistic landmarks of the city, the second round of the Alexandria Short Film Festival wasfew days ago. Twelve Arab countries, including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Morocco, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Palestine, and Algeria participated with 73 short films and documentaries.

Hosted by Alexandria’s Fine Arts Museum, one of the leading cultural and artistic landmarks of the city, the second round of the Alexandria Short Film Festival wasfew days ago. Twelve Arab countries, including Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Morocco, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Palestine, and Algeria participated with 73 short films and documentaries.