Item 15087 wasn’t much to look at, particularly compared to other wonders uncovered from the shipwreck at Antikythera, Greece, in 1901. The underwater excavation revealed gorgeous bronze sculptures, ropes of decadent jewelry and a treasure trove of antique coins.

Item 15087 wasn’t much to look at, particularly compared to other wonders uncovered from the shipwreck at Antikythera, Greece, in 1901. The underwater excavation revealed gorgeous bronze sculptures, ropes of decadent jewelry and a treasure trove of antique coins.

Amid all that splendor, who could have guessed that a shoebox-size mangled bronze machine, its inscriptions barely legible, its gears calcified and corroded, would be the discovery that could captivate scientists for more than a century?

“In this very small volume of messed-up corroded metal you have packed in there enough knowledge to fill several books telling us about ancient technology, ancient science and the way these interacted with the broader culture of the time,” said Alexander Jones, a historian of ancient science at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. “It would be hard to dispute that this is the single most information-rich object that has been uncovered by archaeologists from ancient times.”

Jones is part of an international team of archaeologists, astronomers and historians who have labored for the past 10 years to decipher the mechanism’s many mysteries. The results of their research, including the text of a long explanatory “label” revealed through X-ray analysis, were just published in a special issue of the journal Almagest, which examines the history and philosophy of science.

The findings substantially improve our understanding of the instrument’s origins and purpose, Jones said, offering hints at where and by whom the mechanism was made, and how it might have been used. It looks increasingly like a “philosopher’s guide to the galaxy,” as the Associated Press put it — functioning as a teaching tool, a status symbol and an elaborate celebration of the wonders of ancient science and technology.

[The key to these ancient riddles may lie in a father’s love for his dead son]

In its prime, about 2,100 years ago, the Antikythera (an-ti-KEE-thur-a) Mechanism was a complex, whirling, clockwork instrument comprising at least 30 bronze gears bearing thousands of interlocking tiny teeth. Powered by a single hand crank, the machine modeled the passage of time and the movements of celestial bodies with astonishing precision. It had dials that counted the days according to at least three different calendars, and another that could be used to calculate the timing of the Olympics. Pointers representing the stars and planets revolved around its front face, indicating their position in relation to Earth. A tiny, painted model of the moon rotated on a spindly axis, flashing black and white to mimic the real moon’s waxing and waning.

The sum of all these moving parts was far and away the most sophisticated piece of machinery found from ancient Greece. Nothing like it would appear again until the 14th century, when the earliest geared clocks began to be built in Europe. For the first half century after its discovery, researchers believed that the Antikythera Mechanism had to be something simpler than it seemed, like an astrolabe. How could the Greeks have developed the technology needed to create something so precise, so perfect — only to have it vanish for 1,400 years?

But then Derek de Solla Price, a polymath physicist and science historian at Yale University, traveled to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens to take a look at the enigmatic piece of machinery. In a 1959 paper in Scientific American, he posited that the Antikythera Mechanism was actually the world’s first known “computer,” capable of calculating astronomical events and illustrating the workings of the universe. Over the next two and a half decades, he described in meticulous detail how the mechanism’s diverse functions could be elucidated from the relationships among its intricately interlocked gears.

“Nothing like this instrument is preserved elsewhere. Nothing comparable to it is known from any ancient scientific text or literary allusion,” he wrote.

That wasn’t completely accurate — Cicero wrote of a instrument made by the first century BCE scholar Posidonius of Rhodes that “at each revolution reproduces the same motions of the Sun, the Moon and the five planets that take place in the heavens every day and night.” But it was true that the existence of the Antikythera Mechanism challenged all of scientists’ assumptions about what the ancient Greeks were capable of.

“It is a bit frightening to know that just before the fall of their great civilization the ancient Greeks had come so close to our age, not only in their thought, but also in their scientific technology,” Price said.

Still, the degree of damage to the ancient plates and gears meant that many key questions about the the instrument couldn’t be answered with the technology of Price’s day. Many of the internal workings were clogged or corroded, and the inscriptions were faded or covered up by plates that had been crushed together.

[Broken pottery reveals the sheer devastation caused by the Black Death]

Enter X-ray scanning and imaging technology, which have finally become powerful enough to allow researchers to peer beneath the machine’s calcified surfaces. A decade ago, a diverse group of scientists teamed up to form the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project (AMRP), which would take advantage of that new capability. Their initial results, which illuminated some of the complex inner workings of the machine, were exciting enough to persuade Jones to jump on board.

Fluent in Ancient Greek, he was able to translate the hundreds of new characters revealed in the advanced imaging process.

“Before, we had scraps of the text that was hiding inside these fragments, but there was still a lot of noise,” he said. By combining X-ray images with the impressions left on material that had stuck to the original bronze, “it was like a double jigsaw puzzle that we were able to use for a much clearer reading.”

The main discovery was a more than 3,500-word explanatory text on the main plate of the instrument. It’s not quite an instruction manual — speaking to reporters, Jones’s colleague Mike Edmunds compared it to the long label beside an item in a museum display, according to the AP.

“It’s not telling you how to use it. It says, ‘What you see is such and such,’ rather than, ‘Turn this knob and it shows you something,’ ” he explained.

Other newly translated excerpts included descriptions of a calendar unique to the northern Greek city of Corinth and tiny orbs — now believed lost to the sandy sea bottom — that once moved across the instrument’s face in perfect simulation of the true motion of the five known planets, as well as a mark on the dial that gave the dates of various athletic events, including a relatively minor competition that was held in the city of Rhodes.

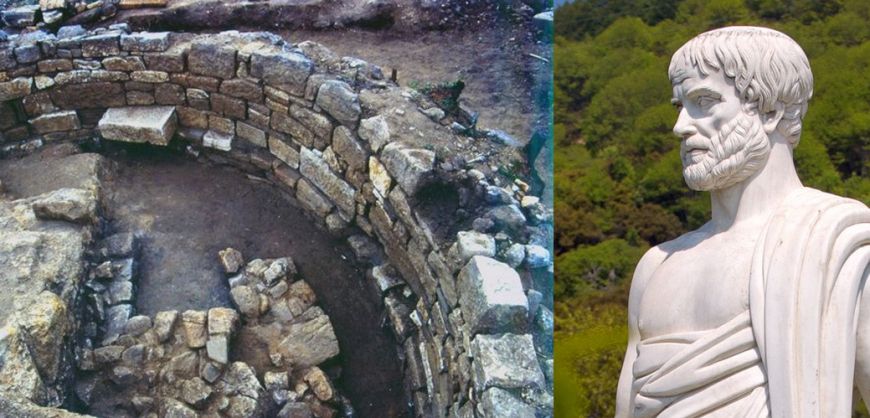

That indicates that the mechanism may have been built in Rhodes — a theory boosted by the fact that much of the pottery uncovered by the shipwreck was characteristic of that city. The craftsmanship of the instrument, and the two distinct sets of handwriting evident in the inscriptions, makes Jones believe that it was a team effort from a small workshop that may have produced similar items. True, no other Antikythera Mechanisms have been found, but that doesn’t mean they never existed. Plenty of ancient bronze artifacts were melted down for scrap (indeed, the mechanism itself may have included material from other objects).

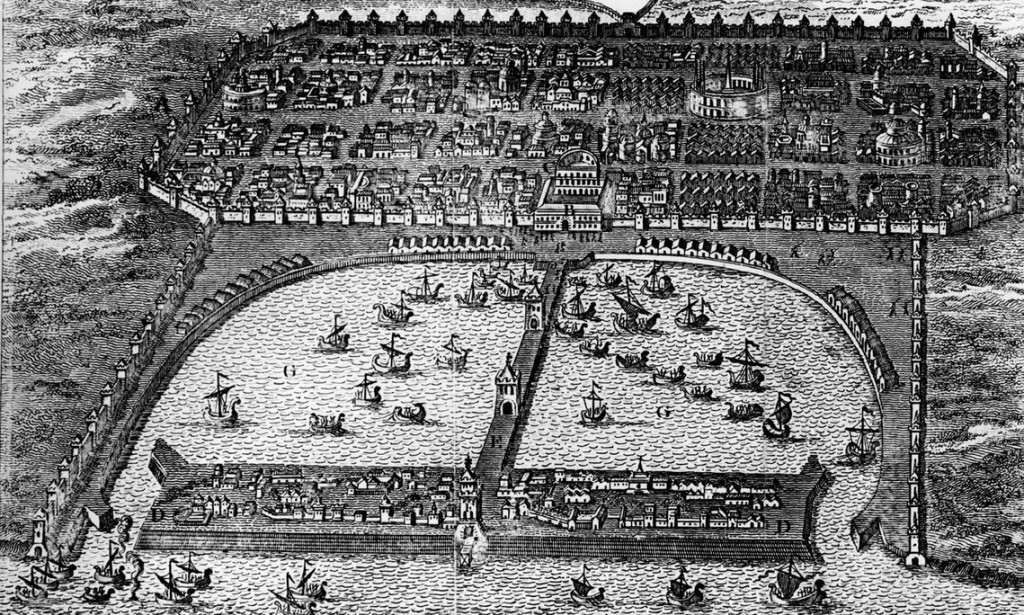

It’s likely that this particular mechanism and the associated Antikythera treasures were en route to a Roman port, where they’d be sold to wealthy nobles who collected rare antiques and intellectual curiosities to adorn their homes.

The elegant complexity of the mechanism – and the use its makers designed it for – are emblematic of the values of the ancient world: For example, a dial that predicts the occurrence of eclipses to the precision of a day also purports to forecast what the color of the moon and weather in the region will be that day. To modern scientists, the three phenomena are entirely distinct from one another — eclipses depend on the predictable movements of the sun, moon and planets, the color of the moon on the scattering of light in Earth’s atmosphere, and the weather on difficult-to-track local conditions. Astronomers may be able to forecast an eclipse years in advance, but there’s no scientific way to know the weather that far out (just ask our friends at the Capital Weather Gang).

But to an ancient Greek, the three concerns were inextricably linked. It was believed that an eclipse could portend a famine, an uprising, a nation’s fate in war.

“Things like eclipses were regarded as having ominous significance,” Jones said. It would have made perfect sense to tie together “these things that are purely astronomical with things that are more cultural, like the Olympic games, and calendars, which is astronomy in service of religion and society, with astrology, which is pure religion.”

That may go some way toward explaining the strange realization Price made more than 50 years ago: The ancient Greeks came dazzlingly close to inventing clockwork centuries sooner than really happened. That they chose to utilize the technology not to mark the minutes, but to plot out their place in the universe, shows just how deeply they regarded the significance of celestial events in their lives.

In a single instrument, Jones said, “they were trying to gather a whole range of things that were part of the Greek experience of the cosmos.”