Tag: Alexandria

-

Plan to restructure Alexandria Port to be delivered in Q1 2016: Minister of Transport

The Port of Singapore is expected to complete its plan to restructure the Alexandria Port’s administration during the first quarter (Q1) of 2016, according to the Minister of Transportation Saad Al-Geioushy. The Port of Singapore is developing a comprehensive plan to reform Egypt’s ports. Alexandria Port is the first port to be addressed in this…

-

Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism: An Archive

Hala Halim, Alexandrian Cosmopolitanism: An Archive. New York: Fordham University Press, 2013. [This review was originally published in the most recent issue of Arab Studies Journal.] Hala Halim’s book is a provocative and erudite study of the modern European literary discourses that have constructed Alexandria as the exemplary site of what we might call cosmopolitan desire. Following…

-

New Provincial Governor in Alexandria

Egypt’s President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi appointed on Saturday 11 new provincial governors. The governors were appointed to the governorates of Alexandria, Suez, Gharbiya, Kafr El-Sheikh, Aswan, Port Said, Sharqiya, Minya, Giza, Qalyoubiya and Beni Suef. Below are brief descriptions of the appointees, five of whom are from police ranks, four from the Armed Forces and two are civil…

-

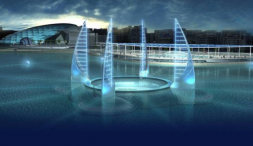

Egypt holds its breath for development of underwater museum

Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Mamdouh al-Damaty announced Sept. 9 that his ministry is planning to develop an underwater antiquities museum — the first of its kind in the world. The museum would be located in Alexandria governorate and would showcase the ancient Egyptian civilization. The project is estimated to cost $150 million. “The museum will reshape…