Tag: Alexandria

-

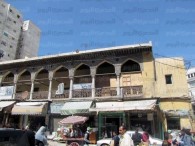

Photographers capture loss of Alexandria’s historic architecture over last 20 years

Photographers Mostafa Mamdouh and Abdallah Hanafy took to Alexandria’s decades-old streets with their cameras in a quest to display how time has taken its toll on the city’s historic landmarks over the last two decades. The photos document the replacement of beautifully-crafted buildings with modern, dreary towers between 1996 and 2016. Mamdouh and Hanafy collected…

-

On Alexandria’s Fouad Street, some have a longing for the elegant past

Along Fouad Street, a Costa coffee shop near old buildings with Italian and French architecture reminds Egyptians that commercial ventures threaten to erase traces of Alexandria’s aristocratic past. ALEXANDRIA, Egypt: Along Fouad Street, a Costa coffee shop near old buildings with Italian and French architecture reminds Egyptians that commercial ventures threaten to erase traces of…

-

The story of cities: how Alexandria laid foundations for the modern world

The secret to Alexandria, if classical historians are to be believed, lies in a golden casket. Studded with jewels and small enough to hold in one’s hands, the casket was a war trophy found in the lodgings of vanquished Persian king Darius III more than 2,300 years ago. The man who defeated Darius, Alexander the…

-

Alexandria’s ancient sites face extinction due to stalled renovation

Archaeological sites in Alexandria are facing ruin, with renovation projects by the Antiquities Ministry covering 13 ancient Islamic, Coptic and Jewish monuments stalled due to a shortfall in funding that stretches back many years. Eighty percent of the province’s sites, meanwhile, have not been touched by conservators for tens of years. Archaeologists have told Al-Masry…