I find the proposition that people should learn Modern Greek because this will improve their English vaguely amusing. Granted there do exist an extremely large number of Greek loanwords and Greek-derived neologisms in the English language but more often than not, English speaking Greeks tend to learn the Greek word AFTER they have discovered its English version. Mourad Didori, Lecturer in Arabic Language Studies applies a similar rationale in his course of lectures You Already Speak Arabic where the number of Arabic words utilised by colloquial English, including apricot, on-loaned from Byzantine Greek, is astounding. While Greek is not the mother of languages as some cultural supremacists would have us believe, it is a little known fact that the Greek language profoundly influenced the languages of the Middle East, especially Arabic and through it, Persian. My first experience of this was when a Persian friend referred to a grape as estafil. Said Persian friend caused my jaw to drop and my mouth to gape open when proceeding to refer to a right angle as a gonia. The borrowings from Greek into the various Iranian languages began in pre-Islamic times, with words such as simino ‘made of silver, silverware,’ attested in Bactrian, didm or diadem attested in Middle Persian, ispir or sphere in Parthian, ‘ysimarye’ for smaragdi or emerald in Pahlavi and yakund, for hyacinth, also in Pahlavi. Most interesting from my point of view is the word palau,originally meaning bowl, from which the word pilaf is derived. This word appears to be a Khotanese borrowing from the Greek word phiale, also meaning bowl.

I find the proposition that people should learn Modern Greek because this will improve their English vaguely amusing. Granted there do exist an extremely large number of Greek loanwords and Greek-derived neologisms in the English language but more often than not, English speaking Greeks tend to learn the Greek word AFTER they have discovered its English version. Mourad Didori, Lecturer in Arabic Language Studies applies a similar rationale in his course of lectures You Already Speak Arabic where the number of Arabic words utilised by colloquial English, including apricot, on-loaned from Byzantine Greek, is astounding. While Greek is not the mother of languages as some cultural supremacists would have us believe, it is a little known fact that the Greek language profoundly influenced the languages of the Middle East, especially Arabic and through it, Persian. My first experience of this was when a Persian friend referred to a grape as estafil. Said Persian friend caused my jaw to drop and my mouth to gape open when proceeding to refer to a right angle as a gonia. The borrowings from Greek into the various Iranian languages began in pre-Islamic times, with words such as simino ‘made of silver, silverware,’ attested in Bactrian, didm or diadem attested in Middle Persian, ispir or sphere in Parthian, ‘ysimarye’ for smaragdi or emerald in Pahlavi and yakund, for hyacinth, also in Pahlavi. Most interesting from my point of view is the word palau,originally meaning bowl, from which the word pilaf is derived. This word appears to be a Khotanese borrowing from the Greek word phiale, also meaning bowl.

Borrowings after the advent of Islam in Persia vary according to genres of texts and to disciplines of learning. Thus in contrast to Islamic religious scholarship (exempting the Koran’s Greek loanwords, which naturally passed into Persian) the syllabus of Aristotelian philosophy, medicine and its ancillary fields, and the occult disciplines-would seem to be primary loci of Greek terminology. Other channels by which Greek words entered Persian were commerce and administration. Eventually, most Greek elements to remain in Persian usage were proper names, especially of ancient authorities, and names of merchandise and of units of measure. Basically any Greek word encountered in Arabic could be incorporated into Persian, whether simply as Arabic or correctly identified as to its Greek origin or intermediate Greek stage.

In addition to division by semantic fields, Greek lexical items in Persian can also be distinguished by trajectory and period of borrowing, considering the marked historical caesurae that delimited periods of potential contact and the fact that, for most of their history, the two linguistic areas of Iranian and Greek were not contiguous. The Muslim conquest and with it the demise of the Sasanian dynasty, and the linguistic shift in Iranian, and the ensuing period of literary latency of what subsequently emerged as New Persian represented a watershed in the introduction of Greek into Iranian. Here a few closely interrelated questions arise, in regard to the period of original borrowing and as to the subsequent destiny of the borrowed lexical items. A fundamental difference exists between the Greek words that entered Persian before the Muslim conquest and the Greek loanwords dating from the post-conquest period. The former passed either directly or via Aramaic from Greek into Pahlavi, the pre-Islamic form of the Persian language while the latter inevitably had Arabic as their proximate origin before entering Persian. This holds true for most of the Greek terms of medicine and pharmacy used in Persian (such as tafisa from the Greek thapsia, and qarabadin, from the Greek graphidion meaning “booklet”).

There are, however, a number of notable exceptions that were passed from Greek into Old and then New Persian directly and are not restricted to use in medical contexts, such as yara (Greek. hiera “holy”), teryak (Greek. theriake “treacle”), ster (Greek. statir “stater,” and deram, derham “dram, dirham,” (Greek. drakhme). Conversely and in greater numbers, Greek medical and medicinal terms, first borrowed during early Byzantine times and then, falling into disuse in Persia were taken over into Arabic and were later re-introduced from Arabic into Persia, such as qawlanj from the Greek kolik meaning colic. From astronomy, examples of comparable late Middle Iranian Greek loanwords which first passed into Arabic before making their way back into Persian are the names Batlamiyus (from the Greek Ptolemaios,) and Majesti (from the Greek Megiste, referring to Ptolemy’s great mathematical work, the “Almagest.”

The reception of large numbers of Greek loan words into Persian is only astounding today, owing to the fact that Iran culturally and politically seems extremely distant and foreign to a modern European-oriented Greece. Yet for most of Greek history, Iran was the other, the utter opposite that fascinated and served to define the Greeks and cause them to construct their own identity. Greek and later Byzantine imperialism, it could be plausibly held, developed from, or aped Persian precedents and it is no coincidence that Greek imperialist expansion primarily took place in the East, over what was once Persian held territory. Cultural exchanges intensified with the transplantation of Greek colonists into Bactria and Byzantine imperial ceremonial was heavily influenced by that of the Persian Sassanian kings, who incidentally referred to their Greek counterparts as “brothers,” considering them to be the only rulers that were their equals. Diplomatic presents usually took the form of the exchanging of texts, engineers and philosophers, while it must be noted that upon the closure of the School of Athens by the Emperor Justinian, Greek philosophers were invited into Persia by its shah, and re-settled in Ctesiphon. Heretical theologians and Greek political refugees were treated likewise so it is no wonder then that the following amazing range of Greek words entered the Persian tongue:

Toponyms: Atiniya “Athens,” Eskandariya “Alexandria,” Ankuriya “Ankara,” Qaysariya “Caesarea,” Rumiya “Rome,” Atrabolos “Tripoli”; Senub “Sinope,” Sivas “Sevasteia.”

Astronomy: Barsavos “Perseus,” Dalfin “Delphinus,” Qanturis “Centaurus,” Qitus “Cetus,” and Qifavus “Cepheus.”

Biblionyms: Abidimiya, from Epidimia “the Epidemics of Hippocrates,” Urganun from Organon “the Organon of Aristotle,” Isaguji from Eisagogi “the Isagoge of Porphyry,” Bari Armanias from Peri Hermineias “Aristotle’s De interpretatione.”

Units of currency and measure: pul from obolos; qesta from xestes, “pint,” qerat from keration “carat.”

General terms: eqlim from klima, “clime,” sabun from sapion, “rotten, putrid,” manjaniq from manganikon, “pulley,” buqalamun from hypokalamon, “moiré cloth,” qamus from okeanos “ocean,” abanus from ebenos “ebony,” tumar from tomarion “document, tract,” qalam from kalamos “reed,” qertas from khartis “sheet of papyrus,” qanun from kanon “straight-edge, rule,”

Medical terms: In addition to Galen and other major authors of works on medicine in Arabic, Dioscorides’s classic on materia medica, provided a wealth of Greek medical terms. Not only was the text studied in Arabic translation, but it was also rendered into Persian. A few samples to permit a glimpse into a rich, existing repertoire: fantasiya for phantasia, “display; imagination,” ilaaus for eileos, “intestinal disease,” faranites for phrenitis, “frenzy,” malikulia for melancholia; anisun for anithon “dill, anise,” qulqas for kolokasi- “Egyptian lotus,” qalqand for khalkanthon, “copper sulphate solution.”

Philosophical terms: hayula for hyle, “wood, timber; matter,” faylasuf for philosophos “philosopher.”

Alchemical terms: eksir for xirion “desiccative powder for wounds,” telasm for telesma “payment, outlay,” and kimia for khimeia “melting; alchemy.”

Religious terms: Eblis for diabolos “slanderer; the Devil,” enjil for euangelion “gospel.”

Of course Persian would get its own back after the fall of Byzantium whereupon through Turkish, a multitude of Persian words would flood the Greek vocabulary, the vast majority of which are still in daily use in the Modern Greek tongue today. Nonetheless, from the first attested appearance of Persian into Greek, being a few garbled words in Aeschylus’ play “the Persians,” until the modern era, there has been a continuous, fascinating and ultimately enriching exchange of culture and vocabulary, absent of which, both our people’s cultures would be much diminished. Next week, a look at Ancient Greek loanwords from Semitic languages. Until then, its an αρραβώνα, which, of course, is an ancient Assyrian word for promise of pledge.

Author: Athanasios Koutoupas

-

Greco-Persian

-

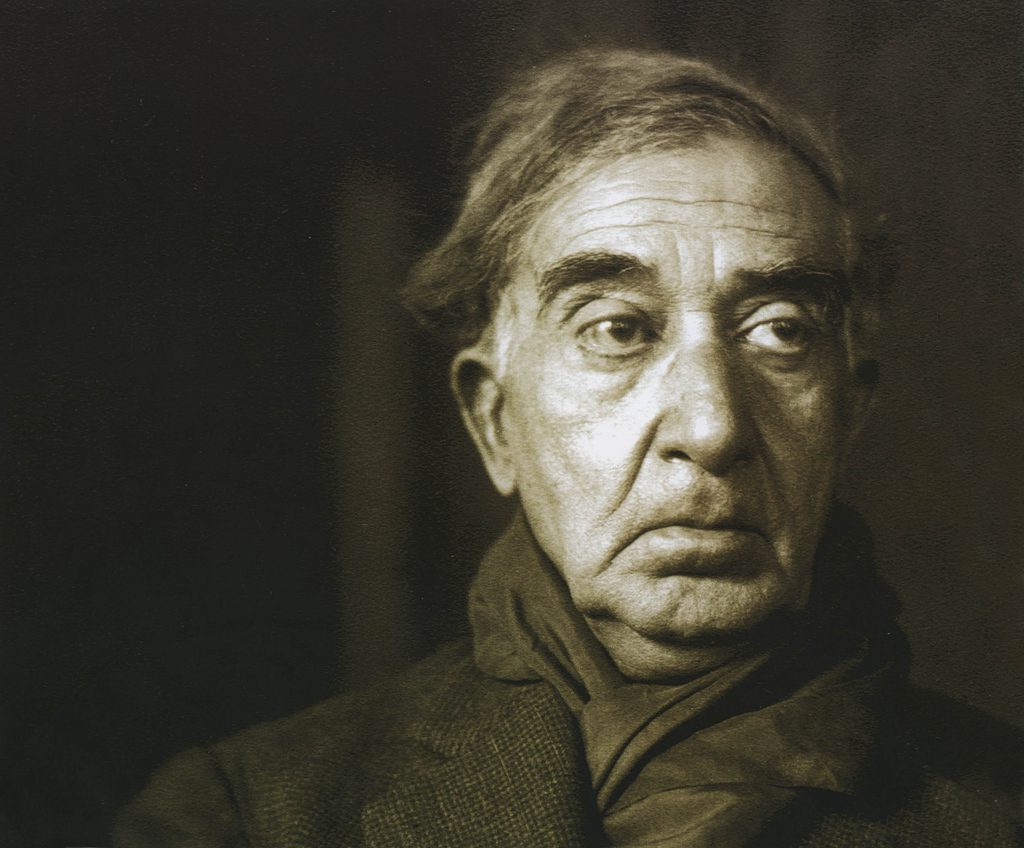

Political Cavafy

Constantine Cavafy is the pre-eminent poet of the Greek diaspora. His poetry seems unchanged by the time. His work, though small compared to that of other fellow artists, is huge in terms of importance and the development it launched in Hellenic poetic events. His poetry was an explosion that precipitated the old poetry, released his tongue and pushed the psyche of the new times – that is his times – introducing a new era in Greek poetry.

Constantine Cavafy is the pre-eminent poet of the Greek diaspora. His poetry seems unchanged by the time. His work, though small compared to that of other fellow artists, is huge in terms of importance and the development it launched in Hellenic poetic events. His poetry was an explosion that precipitated the old poetry, released his tongue and pushed the psyche of the new times – that is his times – introducing a new era in Greek poetry.

His poetry is over-abundant in lessons, elegiac and lyrical, going straight ahead and marking the milestones and bounds through history, a poetry that comes directly from the depths of his soul to conquer the truth and be conquered by life processes. His Logos is fulminant, dramatic, it expresses the impasses of his time struggling to debunk and/or abolish symbols. His poetry is a confession of life pumped by strong emotions and passions, expressed in the most dramatic and unusual way.

Constantine Cavafy’s poetry is a historical research, a deep personal feeling and an inner self-discovery. His poetic language has the rhythm, his walking verse is embedded into the spoken word, just as he thought by himself one should speak the Greek language. There is his own personal drama that wants to hide away and hide himself behind historical moments and events. His poetry is a product of profound and deep philosophical and historical search. Besides, this is why he became a poet quite late, when the time was ready to ripen his wisdom.

However, apart from all these there is the political Cavafy somehow silenced or counterfeited even today. According to the study by Stratis Tsirkas under the title ‘Ο πολιτικός Καβάφης’ the poet “selects the myths of his poems the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman era, not because supposedly in them he could speak more freely about his love, but because, under the guise of imperialism of Rome, there are proportions going with the imperialism of Great Britain in the Eastern Mediterranean, all those years, from the birth of the poet until his death.”

Cavafy had been shocked by an incident when in early June 1906, five British officers went to the small village of Ntensouai to hunt pigeons bred by some fellaheen. The British not only paid no attention to the complaining village official for the inconvenience of the fellaheen caused by previous similar actions but they burned a house with the threshing floor, and with their weapons injured a young fellah and her child. Fellaheen then attacked them with batons and beat them. In their retreat the English shot and wounded four other fellaheen before managed to escape, but went in retaliation. They arrested 52 fellaheen as participants in the riot, and sent them to an emergency court on June 24 in a parody of a trial. The court decision did not provide any appeal or pardon. The court conceded only 30 minutes to apologise to the defendants and refused to accept the testimony of those who said the English first caused the riot and used weapons. On 27 June 1906, the court, in which the majority were British, imposed very strict punishments: Four sentenced to death by hanging, many in forced labour and others in public flogging. The condemned were executed the next day, June 28, at Ntensouai, the area of the episodes, as an example.

Cavafy obviously chose as the title of one of his poems the relevant date of June 26 because he wanted to denounce the inhuman verdict. Particularly, he was deeply moved by the hanging of two very young men, the name of one of which he notes in pencil at the end of the poem, Iousef Hussein Selim. He was 25 years old, but the poet chose the age of 17 years to excite the readers more.

Another aspect of his political and poetic – and not only – stance was that he was asking from 1891 for the return of the Elgin Marbles to their homeland, and by 1893 the unification of Cyprus with Greece.

Through his poetry emerges a clear and readable political stance. Cavafy ridicules, sneers and demystifies the decline of a world that whatever it does, to whatever tricks it resorts, is doomed to fall irrevocably. In his poems he is using the conquest of Greek and Hellenistic land by the Roman Empire to express his opposition toward the sovereignty of England at the time.

One of the most serious scholars of Cavafy’s work (and also an Alexandrian poet, writer, scholar and writer), George Vrisimitzakis, in his work Η πολιτική του Καβάφη” says that “the policy of Cavafy is a political frustration, but also an effort of adjustment. His policy is not a policy conquerors use when undergoing expansion, but use it when once they finished conquering are struggling for not to be conquered themselves, not to be assimilated, not to be absorbed by upcoming new enemies.”

It must be emphasized here that George Vrisimitzakis -in my opinion, an equally significant, but unfortunately forgotten figure of the Greek Letters of Alexandria during this period- was the first to speak about the political attitude of Cavafy, as the poet was still alive. In 1926 (seven years before the poet’s death, in 1933), George Vrisimitzakis, apparently with the consent and approval of the poet himself, gave the small but rather remarkable study entitled “Η πολιτική του Καβάφη”, in which analyzes the Cavafy’s political stance as “a trim adjustment policy,” a policy not combative and rebellious, but defensive, which in principle designed to survival and then preserve the identity and integrity of the oppressed.

G. P. Savvides, writes that Cavafy is a political poet in the sense of its historical dimension and his social consciousness raised in the past and reflected in the future of Hellenism as a privileged expression of the Mediterranean Culture. Like any worthy artist, Cavafy can only be a witness of his nation and his time.” (“Μικρά Καβαφικά”, Volume II). “Was politicized, but not a partisan. He was deifying nor persons, nor statements” continues G. P. Savvides. (In the same work).

During the same period in Greece Cavafy accepts relentless criticism and rejection not only from conservatives and irredentist critics and writers who considered him as a dangerous man (Fotos Politis, George Theotokas, Elias Voutieridis and even Kostis Palamas) but also from militants of the Left who fought him fiercely. Costas Varnalis saw only negatives in Cavafy’s poetry (faulty technique, false language, poor vocabulary, lack of musicality), Markos Avgeris resembles him as a… squirrel in his cage, morally isolated, and away from the adventures of the society, and even Giannis Psycharis described him as a… jackass of the demotic language.

But exactly 20 years after the study of G. Vrisimitzakis to the defenders of Cavafy (Gr. Xenopoulos, Alkis Thrylos, Galatea Kazantzakis, Angelos Sikelianos, Tellos Agras) George Seferis been added, who on December 11, 1946, in a lecture at British Council on “CP Cavafy, T. S. Elliott: parallels”, presented another Cavafy correlating his epigram “Those who fought for the Achaean League” (in Ed. Keeley’s translation) with the Asia Minor Catastrophe. The ice had now begun to break.

In 1958 Stratis Tsirkas by his work “Ο Καβάφης και η εποχή του” showed irrefutable evidence of how little self-centered was the poetry of Cavafy, how tied to specific events of the era and of his city was. Since new valuable works for the poetry and the political attitude of Constantine Cavafy that saw the light of day as the work of Stratis Tsirkas “Ο πολιτικός Καβάφης” in 1971, but also lectures, symposia and scientific interventions mainly by G. P. Savvides, who is also the owner of the archive of C P. Cavafy, Dimitris N. Maronitis and others.

Bibliography

Στρατής Τσίρκας, Ο Καβάφης και η εποχή του, εκδόσεις Κέδρος,1958

Στρατής Τσίρκας, Ο πολιτικός Καβάφης, εκδόσεις Κέδρος,1980

Γ. Βρισιμιτζάκης, Η πολιτική του Καβάφη, Επιθεώρηση Τέχνης

Γ.Π. Σαββίδης, Μικρά Καβαφικά, εκδόσεις Ερμής,1985. -

Constantine Cavafy: The Poet of the Diaspora

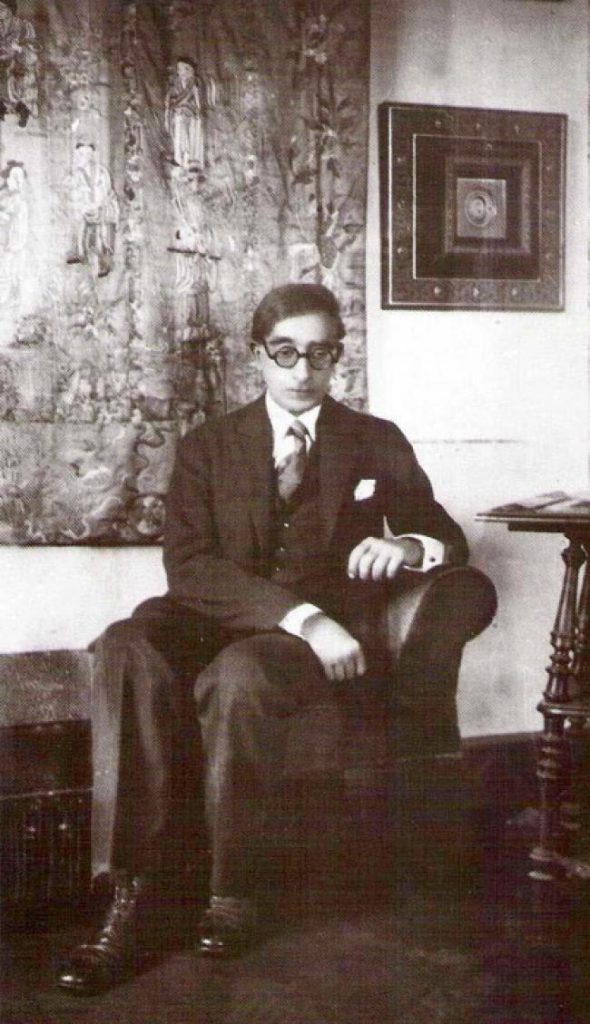

I am from Constantinople by descent but was born in Alexandria in a house on Sheriff Street. I was very young when I left for England where I spent much of my childhood. I returned to that place when I was older but only after having lived in France for a spell and after passing a couple of my adolescent years in Istanbul. I haven’t visited Greece in many years and my last employment was in the Government Office of the Ministry of Public Works of Egypt. I know English, French and a little Italian.

I am from Constantinople by descent but was born in Alexandria in a house on Sheriff Street. I was very young when I left for England where I spent much of my childhood. I returned to that place when I was older but only after having lived in France for a spell and after passing a couple of my adolescent years in Istanbul. I haven’t visited Greece in many years and my last employment was in the Government Office of the Ministry of Public Works of Egypt. I know English, French and a little Italian.This is the simple, personal biographical note left by the famous Greek poet, Constantine Petrou Photiades Cavafy (1863-1933), who was born in Alexandria, lived between England, France and Istanbul and visited Greece on occasion. He is remembered for his humble, solitary lifestyle and the underlying, implied homosexuality in his writing. He is revered for the mastery of a poetic style that is, at once, very plain and unassuming but, at the same time, conceals an enormous symbolism.

This year marked the 150th anniversary of Cavafy’s birth, which was celebrated with great pomp and circumstance in Greece and in many Greek communities and universities abroad. Major events feting the renowned poet took place in the United States, in Canada and in Australia, showcasing his poetry and outlining its impact on literature.

2013 was also the year in which the Cavafy Archive containing the bulk of his documents and personal items were acquired by the Onassis Foundation, bringing this invaluable historical and literary treasure under the protection of the reputed organization and keeping it from being sold abroad. Organized and concentrated in a unique and meticulous manner, Cavafy wanted his archives to facilitate future researchers of his work.

His writings have been the subject of lengthy studies around the globe and his poetry has been translated into many languages including French, English, German, Italian, Spanish and Japanese. His use of the ironic element in combination with tragic reality, known as “Cavafy’s irony,” has become the benchmark for the myriad of poets that were influenced by him.

Surprisingly, recognition did not come swiftly for Cavafy in Greece, perhaps due to his use of the demotic and the charming simplicity of his words that appear as if they were penned by a child. Heavily inspired by Greek and Roman history and myths, Cavafy’s memories are timeless, combining places and cultures. His poetry may appear trapped in its eastern roots, yet it often flirts with the western bourgeoisie of Europe.

Yes, Cavafy was a man of the world, a true representative of the Hellenic Diaspora. His reality may have been that of a common civil servant who wrote in a house above a brothel in Alexandria but his words bear the connotation of a much-travelled life. The journey, the city, the walls and his repetitive, daily routine are all prevalent in his work where an effortless melancholy and compromise is evident. He is excited by beauty but tends to fear it. Incompatible with these restrictions, Cavafy likes to travel in time, to places. Desperate and restless as all poets, he remains optimistic. His words often lead to deadlock with fateful conclusions but his ironic vein is there to awaken a smirk on his reader’s lips.

As he writes in The City, one of my favorite poems:

The City

You said, “I will go to another land, I will go to another sea.

Another city will be found, better than this.

Every effort of mine is condemned by fate;

and my heart is-like a corpse-buried.

How long in this wasteland will my mind remain.

Wherever I turn my eyes, wherever I may look

I see the black ruins of my life here,

where I spent so many years, and ruined and wasted.”

New lands you will not find, you will not find other seas.

The city will follow you. You will roam the same

streets. And you will age in the same neighborhoods;

in these same houses you will grow gray.

Always you will arrive in this city. To another land-do not hope-

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you have ruined your life here

in this little corner, you have destroyed it in the whole world. -

Cavafy’s Cultural Politics and the Poetics of Liminality

Probing the work of C. P. Cavafy has been intriguing for me, not only because he is one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century European aesthetic culture, but also for another reason: as Cavafy records in his diary of his first trip to Greece in 1901 (written in English), he was positively predisposed toward the work of Georgios Roilos, an influential late nineteenth-early twentieth-century Greek painter, among the first to introduce impressionism in Greece, a professor and mentor of, among other artists, Giorgio de Chirico. In his diary entry for June 28, 1901, Cavafy reports that he visited Roilos in his studio and enjoyed his painting “The Battle of Pharsala”: “At 4:30 I took the direction of the Polytechneion. The first person I met in the Odos Patision was Tsocopoulo [sic], who accompanied me to the Polytechneion and conducted me to the painter Roilos’s study to see this artist’s great picture ‘The Battle of Pharsala.’” That encounter of the poet with the painter is one of the stories often narrated at home when I was a child — stories that later determined my scholarly attachment to cultural history and art.

Probing the work of C. P. Cavafy has been intriguing for me, not only because he is one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century European aesthetic culture, but also for another reason: as Cavafy records in his diary of his first trip to Greece in 1901 (written in English), he was positively predisposed toward the work of Georgios Roilos, an influential late nineteenth-early twentieth-century Greek painter, among the first to introduce impressionism in Greece, a professor and mentor of, among other artists, Giorgio de Chirico. In his diary entry for June 28, 1901, Cavafy reports that he visited Roilos in his studio and enjoyed his painting “The Battle of Pharsala”: “At 4:30 I took the direction of the Polytechneion. The first person I met in the Odos Patision was Tsocopoulo [sic], who accompanied me to the Polytechneion and conducted me to the painter Roilos’s study to see this artist’s great picture ‘The Battle of Pharsala.’” That encounter of the poet with the painter is one of the stories often narrated at home when I was a child — stories that later determined my scholarly attachment to cultural history and art.Cavafy was born (in 1863) and spent most of his life in the periphery of the Greek-speaking world, in Alexandria, Egypt, where he died in 1933. Although a fervent patriot and lover of all things Greek, his cosmopolitan experiences (he spent some years of his childhood in England and of his late adolescence in Constantinople) and especially his diasporic mentality contributed to his critical approach to aspects of the cultural and political life of mainland Greece. His stance toward cultural matters, history, and morality was greatly influenced, on the one hand, by his multicultural open-mindedness, and, on the other, by his own marked (geographical but, more crucially, I believe, socio-aesthetic) liminality.

Cavafy’s diasporic experience contributed to the formation of his overall cultural politics, which continues to inspire an exceptionally large number of readers, poets, scholars, intellectuals, and activists throughout the world. The everlasting appeal of his discourse to contemporary readership was evocatively demonstrated and celebrated at an event I organized at Harvard last year to celebrate the end of the so-called Cavafy Year: at that event, in which no less than 27 Harvard colleagues and graduate students participated as readers, one of his most famous poems, “Ithaca,” was recited in 27 different languages!

In general, cultural politics is to be understood as a two-way process: it refers, on the one hand, to the impact of political ideologies and practices on the production and consumption of cultural commodities; and, on the other, to the intricate ways in which the latter respond to, and even shape, aspects of the former. Cultural politics and Cavafy can be explored from many different, but, essentially, complementary perspectives. For instance, it can address the following questions: how his work is received by agents of politically determined or at least politically informed ideological discourses and practices (nationalism, postcolonialism, gender and queer studies, etc.); or how specific poems may reflect specific political and social concerns in his contemporary Alexandrian or wider Greek contexts; or, how the content of his mature work (produced and published from the late 1890s onward but especially after 1911) as well as his stylistic choices, especially the gradual development of a poetic discourse that was, at least according to the established criteria of poeticity of the time, closer to prose than to poetry (and as such, an inherently liminal discourse), undermined dominant socio-aesthetic premises. My emphasis in this piece is on these last aspects of the complex topic “Cavafy and cultural politics,” which may be relevant to broader debates in related intellectual and scholarly fields as well.

Cavafy, who had famously declared that, if he were not a poet he would have most happily been a historian, demonstrates an astute historical, political, and, of course, aesthetic sensitivity throughout his (published and unpublished) work, especially from the middle of (what I have called) his allegorical period (1890s) onward. By contrast to cultural and ideological paradigms dominating his contemporary Greek and broader European intellectual production, Cavafy was particularly attracted not so much to the achievements of the famous classical past as, rather, to transitional periods of ancient and medieval Greek history: the era following Alexander the Great’s expeditions to the East and the establishment of the Hellenistic kingdoms; late antiquity; Byzantium.

Not unlike betwixt-and-between phases — more often than not ritually negotiated — in an individual’s or a community’s life, such periods frequently bear the symptoms of ambivalent liminality: to a great extent determined by critical, potentially both destructive and creative, “risky” and reinvigorating, tensions between opposing conceptual, ideological, and broader sociocultural categories (familiar/unfamiliar; foreign/domestic; us/others; past/present;), liminal eras in history, at least as perceived and approached by Cavafy, are, to a lesser or greater degree, marked by open-endedness, inclusiveness (syncretism), and what I prefer to call amphoteroglossic (“double-tongued,” i.e. ambivalent) fluidity.

Cavafy’s subversion of moral and gender hierarchies, too, as this was powerfully manifested through his outspoken celebration of homoerotic desire mainly in his mature years, decisively contributed to the liminality of his overall cultural politics and poetic revolution. His highly original, often “secularized” redefinition of aspects of the aesthetics and ethics of the so-called “Hellenic love,” as these had been developed especially in Western European (notably British) aestheticism, was based on a radical destabilization of ethical, cultural, and even economic principles of post-industrialist European societies. As I have argued elsewhere, his celebration of both homoerotic desire and poetic creativity were conceptualized and articulated in terms of what I call an “anti-economy of jouissance,” a kind of “economy” that prioritizes excess, consumption, and (self-)expenditure at the expense of the dominant economic principles of profit and utility.

For Cavafy, poetry constitutes a daring exemplification of such an anti-economy, since it often involves creation through (self-)expenditure and loss — or, in terms of ritual poetics, through self-sacrifice. His conceptualization of poetic creativity as an instantiation of a broader economico-erotic liminality is eloquently expressed in a poem that bears the characteristically ritualistic title “Passage,” in which initiation into the “world” of poetry is described as a rite of passage indeed. That poem, which was written in 1914 and published in 1917, reads as follows (in my rather literal translation):

Those things that as a student he coyly imagined are opened,

revealed before him. And he keeps roaming and staying up at night,

and being led astray. And as is (for our art) right,

hedonic pleasure enjoys

his blood, fresh and warm. An unlawful

erotic intoxication defeats his body; and his youthful

limbs succumb to it.

And thus, a simple youth

becomes worthy for us to see, and though the Sublime

World of Poetry he, too, one moment passes—

the aesthetic youth with blood fresh and warm.